It’s mid-January now, just past the Wolf moon, or Quiet moon, which is already waning. Last Sunday, as the pink light of dusk spread out across the sky, I went to our bedroom window to wait for the moonrise. I was feeling very quiet indeed. It had been a busy weekend after a busy week, and our neighbors had dropped by again. My husband put on the coffee while our three kids, plus the two neighbor kids, ran in circles around the house. One was dressed as Spiderman, another as Batman, another in a black cat mask with long whiskers (though was curiously barking like a dog), and another with a rainbow flag tied around her shoulders like a cape, while the youngest was content to simply be included. All were squealing and sometimes crying, but mostly laughing.

Our home was pulsing with sounds I know I’ll look back on longingly one day, but I’d been entertaining people all weekend, and by Sunday evening, I was profoundly exhausted. All I wanted was to fall back into the sofa and read a good book or watch a movie, or at the very least take a moment to hear what my soul was trying to say. And what it said when I sat down by the window was, You’re running on empty.

And then I saw it, rising in its whole round glory from behind the craggy cliffs. The Wolf moon.

I was empty, and it was full.

Earlier that day, we’d taken the kids out sledding in the forest. Some trails were too hard to sled on, so we traveled atop the frozen sea, right along the edges so that we could easily jump back onto land whenever the ice got too thin. The sea carried us for a long way though. Past the high cliffs, out of the thick forest, into an open meadow, where we decided it was time to step back onto land. That’s when I saw them.

Tracks. And I mean these were big, beautiful tracks.

I wasn’t sure whose tracks they were but my first instinct said Wolf.

The animal gait was straight. There was no sign of meandering or exploring. This animal knew exactly where it was going. There was no dragging either, the imprint was clean. Otherwise I might have written them off as Fox or Dog. I also looked around for human tracks but never found any.

What stumped me was how shallow the tracks were, barely sinking into the snow, which hinted towards a smaller, more lightweight animal.

Also, the tracks were solo. Just one animal, which is unusual for wolves who thrive in packs. Except around this time of year actually, when it’s common for a full-grown wolf to leave its pack in hopes of finding a mate and starting its own pack, or family, which is essentially what a pack is, two wolf parents and their offspring. The innate drive to disperse and find a mate outside of the pack protects against inbreeding, keeps the wolf population healthy and strong. The endeavor is both necessary and risky. A lone wolf doesn’t have the protection and shared resources of its pack. He or she often gets lonely too. Sometimes, to communicate its loneliness and desire to mate, a lone wolf will throw its head back and howl – a howl that can pierce though forests and ride across open land for many miles.

Perhaps native people who lived so attuned to nature heard the howling of lonely wolves this time of year, and thus the January came to be called the Wolf moon.

I’d always heard it was due to the scarcity of food available in mid-winter. Turns out this is wrong. There are many reasons why wolves howl, but hunger is not one of them.

I’m ashamed it’s taken me 43 years to learn this untruth. Mostly I’m ashamed that I never thought to question it. That I know so little about wild animals, even those I share land with. That I’m so disconnected from all these wild mysteries and intelligences that are literally right under my feet.

Animal tracking is something I’ve become keenly interested in since when we moved onto our little plot right on the edge of a nature reserve. Here, dense forest meets the sea. Large swathes of coastal meadows roll into grazing pastures. A river runs through it at several turns. This is a place that invites many different types of wildlife.

It was only the plants I saw at first. I’ve spent years foraging and learning from wild plants, not only to eat but also to weave baskets, dye textiles, make natural medicines and cosmetics with. There are dozens of flowers, trees, bushes, berries, roots and mushrooms that are so dear to me that when we first arrived here and I met them out on the land, I felt immediately at home.

My first animal tracking experience began soon after – and with a very unexpected animal. Spider. I became absolutely fascinated with the spiders who lived under the awnings of our house. I spent a large chunk of my summer observing them “with attentiveness bordering on devoutness.” Especially during those liminal dusk hours between day and night when spiders began to weave their webs. It wasn’t long until they began to draw me out at night too, into deeper and darker hours, to watch them hunt. My fascination continued on into the autumn as spiders laid their egg sacs and guarded them with their lives. Their behavior began to shift dramatically at this point. I followed their silk highways away from our house, out into the world where they found shelter for the winter. By this time, they’d already given me so much insight into myself and the culture I’m embedded within. They’d dispelled my fears and helped me understand their role here on this planet – which somehow helped me remember my own role as well.

Nature is often a mirror, isn’t it? A glimpse of the human psyche. For better or worse.

There was another animal here when we arrived, and I was quickly forming a relationship to it too. Sheep. A large flock of sheep pastured on the land just next to our house and went to the forest to sleep every night. As they ate through all the grass and herbage in the paddock, they started searching the forest for food too. We often met them out there, walked with them along their trodden paths through the underbrush, trying our best, at first, to step around their black stool pellets all over the ground. As I looked for their stool pellets, I began to notice other types of stool too, or scat it’s called. And after rainy spells, I began to notice other tracks in the mud.

Who else do we share this land with? I wondered.

I knew about Fox, because they’ve been responsible for the disappearance of many a’hen around here. But I’d never seen Fox and had no idea what their tracks or scat looked like.

I knew about Beaver too. Just a short walk along the river, and you’ll immediately see the work of Beaver. Sometimes their work is so recent that the exposed wood is still orange and aromatic. My boys have been determined to find a beaver, but after several dozens of walks along the river, we’ve never seen one.

I also knew about Boar, because they came out of the forest when the corn fields were being harvested, devoured all the kernels left in the tractor’s wake.

Oh Deer, Deer, Deer. They’re everywhere. Especially in the half hour before sunrise, I’m often arrested by their gorgeously lithe bodies. I’d followed their tracks criss-crossing through the forest before, always going between open fields, and had even become confident in the different signs and tracks left by different types of deer.

I’d heard about Moose in this area yet never saw them until the snow fell, and then they didn’t hesitate to come all the way to the edge of the road as if completely undisturbed by motorized vehicles.

Rabbit is here, of course, and so many many birds.

But Wolf?

My neighbor told me once that wolves live outside of his mother’s town. “Which town is that?” I asked. “It’s about 25 minutes that way,” he said, pointing west. “Sometimes you can hear them howling from here.”

I wanted to hear those howls. I wanted to know all the wild animals – beyond just knowing about them. To know which kinds of rabbit, which species of birds, even rodents. From small to large animal, I wanted to know what their footsteps looked like and how to follow them, to know their challenges and even their joys.

I couldn’t say why. It’s not like I need any animal tracking skills – or any knowledge about nature, actually – for my survival, not anymore.

There was some essential thing I felt I was missing.

Craig Foster, filmmaker and ocean conservationist, says that animal tracking is the oldest language in the world.

“Our species, Homo sapiens, has been around for approximately 300,000 years,” said Foster in an interview. “And for all of that time, except for the last 2 or 3% of that time on this planet, we have been conversant in this oldest language. We’ve been able to follow animal tracks, see an enormous range of signs left by animals. Because that’s been an intricate part of our survival.”

Language. Maybe that’s what I was missing.

It was a language I’d lost.

From my years studying Sociology, I know about the impact of loss of language. I knew that indigenous people who were forbidden to speak their language and only speak a colonizer’s language could suffer extreme mental breakdowns. “Indigenous youth with less knowledge of their native language are 6 times more likely to have suicidal ideation than those with greater language knowledge,” a medical journal states.

Language is so much more than intellectual comprehension. It is tied to one’s identity and traditions, both individually and culturally. When a language goes, so do certain ideas and ways of perceiving the world.

Loss of language is just, if not more, damaging to the psyche than physical displacement. Though the two are interrelated of course, since to remove people from their land is to remove them from their place-based relationships, it is to stop that conversation between people and animals and plants, rocks and water. Which leads to another degree of language loss.

That’s essentially what’s happened to us all, I guess. We no longer commune with the living world. We’re so tame now. Forever barred from that animal way of being. To re-forge those relationships and recover that language would require concerted time and effort on our part.

And if animal tracking isn’t necessary for our survival anymore, why bother with it? Perhaps it died out naturally, as things do. That’s the nature of life. We have to be willing to let go of some skills in order to develop new ones.

What I’ve found, however, is that the urge still seems to be alive in me. Early last summer, when I found a dead sheep in the forest, I didn’t just throw my hands up and say, well that’s that. I began to unravel the mystery. Instinctively, I searched the area for tracks and signs. I analyzed the way the sheep had been attacked. I didn’t know what anything meant, but somehow I knew what to look for. Deep in my bones, I still knew how to read the landscape. In the same that way that I still know how to read a sheet of piano music, although I’m so out of practice now, my piano playing is rusty and painfully slow, but my fingers still know the language.

I cannot tell you how deeply satisfying it is to sit down at a piano and enter into that language. It’s literally magic. And the more I practice, the more intuitive that language becomes so that I don’t have to think at all. I just play. This is the reward of spending decades of my life training at the piano.

Imagine, we have hundreds of thousands of years of experience in animal tracking stored somewhere in our unconscious. We might be many generations out of practice now, but it lives on. The reason for our survival and the very foundation of our identity is built upon our ancestor’s connection to nature and their relationship to the natural world.

I find that my children have a natural knack for it too.

Just last weekend I took my two oldest boys out for a walk. We were headed to the forest, about to cross the bridge over the river when Bastian, my 4-year old, said, “Let’s go see the sheep!”

We still visit her often, the mama sheep who passed away a couple of days after birthing two lambs last autumn. Her body was removed, but her coat of wool was left behind. Her spirit is there too. I can feel her everywhere as I approach the spot where she died.

My boys knew the way. They walked right to the spot. Bastian bent down and brushed snow away from the black wool. It’s matted and heavy with moisture now.

I noticed Axel looking around as if surveying the area. I wondered if he sensed her spirit too. I asked, “Are you looking for something?”

He answered, “I wonder why she chose this spot.”

His question surprised me. It seemed remarkably astute for a boy just shy of 8, and yet maybe not. Maybe it was exactly the sort of question he should’ve been asking.

I’d asked myself the same thing before too. Of all the places she could have hobbled to to die, why this spot? It was only when I got completely still and quiet that I noticed she’d laid down right between two enormous trees. Behind the trees, the river gurgles. It’s such a soothing sound, the river. Barely moving below the ice now, but I can still hear it. In August, it would have murmured much more on the surface. And the trees would have been full of leaves that rustled into the wind.

Axel nodded and added, “These big trees would have made a lot of shade too.”

Yes, of course.

The language lives in us all. The curiosity and passion to know is in us all. The need to feel connected and in relationship, it burns and yearns within us all.

I listened to a fantastic podcast called Tracking Our Roots in Nature in which Jon Young gave me some words for the pull I’ve felt towards animals lately. He says that tracking is the art of:

- wanting to truly know and understand other life forms here, who they are and what they bring, the role they play, what they enjoy in order to experience profound connection and belonging

- asking the good questions, the sacred questions, and being able to let go after asking

- trusting all your senses and going into that silent place that animal language get us to

- learning to trust your gut, your instincts, your body’s radar to lead to you to the right place at the right time

The whole world becomes alive to magic, he said. There will be constant occurrences which may feel like coincidences, and yet how many times will you call them a coincidence? What happens when 99 coincidences becomes 100? It might be time to wake up the magic.

Magic is my word for 2025.

The year of magical thinking.

And yet it’s not thinking. There’s very little thinking involved. If you think too much, you lose the tracks.

That day last summer when I found the sheep legs in the forest and realized that it had been attacked by a predator, I got all my clues together and decided to ask a neighbor if he had any insights. But he shrugged it off and said it was probably just an accident.

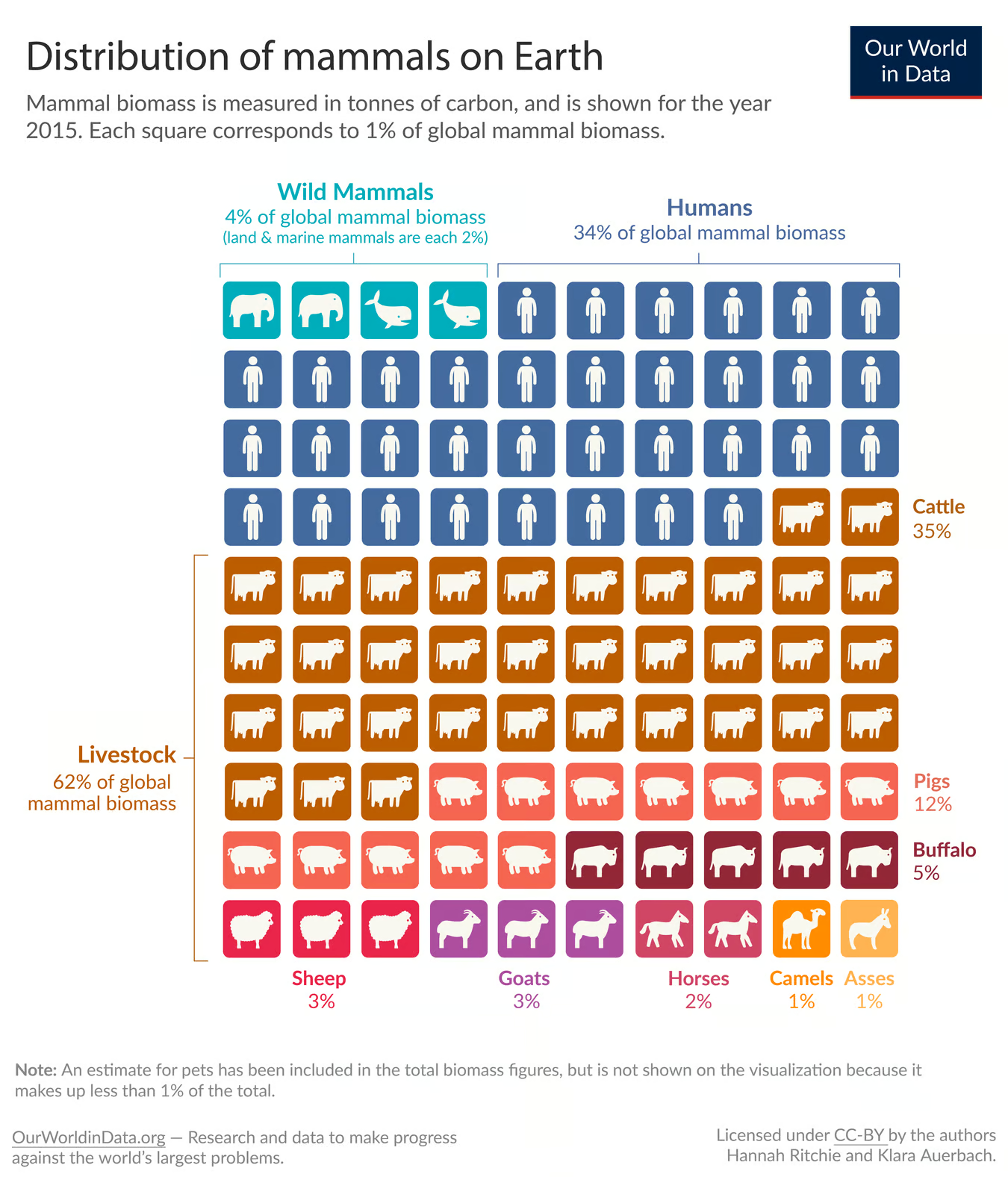

“There’s not much wildlife left here,” he explained. “No different in this area than in the rest of the world.” I must have looked confused, because, with a sense of pity in his eyes, he spat out some statistics, gave me the real hard facts. Only 3 or 4% of mammals alive today are still wild, he said. Almost all of the animals on this planet today are humans and our agricultural livestock.

I thought it couldn’t be true, but some research confirmed everything my neighbor said.

I even came to one study that put the numbers into a graph so large my eyes could not look away.

Same with the bird population. For every 1 wild bird, there are 3 caged poultry birds. In other words, the majority of birds alive on this planet today belong to human industry.

Something in me tore open that day.

As I sat in my bedroom window last Sunday evening watching the Wolf moon rise, the wound in me throbbed. Only 4% animals are wild, it said with each pulse.

“The doors to the world of the wild Self are few but precious. If you have a deep scar, that is the door. If you have an old, old story, that is the door.”

– from Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estés

I thought about the tracks we’d seen in the snow and looked toward the place where we’d found them. No matter which animal it had been, it was a rare thing. It was wildly alive and intelligent, and I wanted to return to that spot. Maybe in the half-light of dusk I’d find more clues.

Suddenly it felt like I could not sit inside the window speculating anymore. I could not stand in the kitchen exchanging pleasantries and drinking lukewarm tea with the neighbors. I needed to get out of the house. Follow my body. If wild animals are rare these days, then imagine what the statistics are for wild humans.

I imagined myself walking out into the kitchen and smiling at the adult men there, politely excusing myself. I imagined calmly putting on my boots and jacket, giving my kids a wink on my way out. I wouldn’t tell them where I was going because they would want to come with me, and I needed to go alone tonight.

Walking out of our driveway, I’d enter the nature reserve, take off in a sprint. The moon would follow me above. A lone wolf it was, and I was too. Both of us rising, shining.

But of course the real lone wolf – if that’s even what it was – would be far gone by now. They can travel 10 or more miles per day in this stage of their lives, hunting just enough food to stay alive, hunting more than anything the impulse to mate and start a family.

I already had my family, and it actually was time to re-join them and our neighbors in the kitchen. I’d already displayed enough anti-social behavior by taking a 10-minute break. When I first sat down at the window, I was thinking how nice it would be to read a book or watch a movie all by myself, but that desire was gone now. It had been what I’d wanted, but not what I’d needed.

What I’d needed was to a chance to connect with the wildness within. I can’t follow every bodily impulse, and I shouldn’t, but I can rest assured that she’s always here, that I’m part of something as new as tomorrow and as old as the beginning of time. For that brief flash of a moment, if only in my imagination, I followed her tracks.

One day I’ll be able to track her all the way.

I’ll know her scent the way I know my own children’s. I’ll know where she’s been and who she’s been with. It will tell me where she’s going next.

I’ll track her when she’s wounded, I’ll know it’s her by the hue of her blood and the shape of her howl.

I’ll know when she’s hungry and what she’s hungry for.

I’ll learn to track her in all seasons – not just snow and mud, but also in the faintest of winds.

I’ll be ready to run after her all day, to outrun my own thirst until at last the animal has taken me to the farthest edge, where mind and body meet like the sea and shore.

Something tells me I’ll end up exactly where I began.

In the heart of the wild mystery it’s always been.

xx

Beth